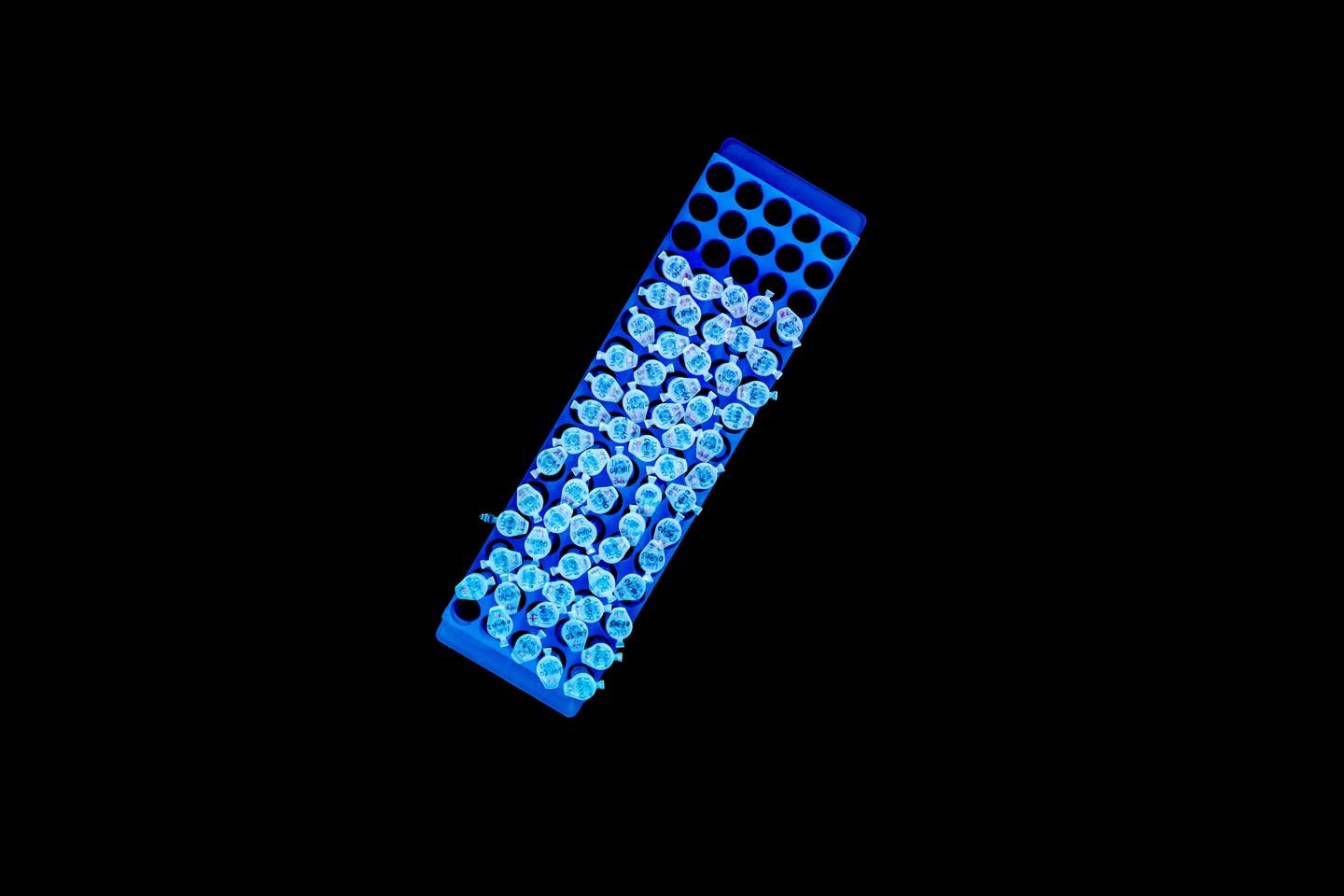

Samples in United Neuroscience’s laboratory

In the autumn of 2010, Mei Mei Hu, a management consultant for McKinsey in New York, received an unexpected invitation from her mother, Chang Yi Wang, asking her to join her for Christmas in Shanghai.

Mei Mei always had a complicated relationship with her mother. “Chang Yi is very particular and exacting – which is part of her genius,” Mei Mei explains, sitting in a restaurant in Cold Spring Harbor, a former whaling community on Long Island’s North Shore. She’s tall and slim, with long dark hair pulled back in an unruly pony tail. She was born in Great Neck, a suburb of New York, in 1983. A few years later, her family moved to a large colonial house in Cold Spring Harbor. “I remember coming back from school with a test score of 98 per cent and all she said was – next time, kill those last two points,” she grins, exasperated. “So, much to her surprise, I avoided science in school. I spent the rest of my life trying not to work with my parents.” Instead, she studied economics at the University of Pennsylvania, where she met her husband, then trained to be a lawyer, and has spent most of her career as a management consultant.

Chang Yi, on the other hand, is something of a legend in the fields of immunology and biochemistry: she has two PhDs, developed tests for HIV and Hepatitis C, and conducted pioneering research into an HIV vaccine. She is also the co-founder of United Biomedical, a sprawling drug development company with offices and labs in the US, Taiwan and mainland China. Mei Mei hadn’t really talked to her mother about United Biomedical for some time, and she was keen to remain ignorant about the company’s affairs. “Ever since I’ve been small my parents have worked together with very little boundary between personal life and work life,” she says. “If they’re stressed at work, you know about it. It’s one of the reasons I always promised I would never work with my mother.”

Over that Christmas in 2010, however, Mei Mei gradually realised, during long conversations with her mother at the dinner table, that the company was facing serious legal issues. “I just listened and talked to her and discovered there were shareholder disputes and legal actions that were taking up her time and money,” she explains. “If they went badly, the company would be in trouble.”

Mei Mei began poring over the company’s documents and what she found amazed her. United Biomedical was a company with only a few hundred employees and yet it was involved in animal and human healthcare: making generic drugs, monoclonal antibodies, blood tests for HIV and vaccines for foot-and-mouth disease. Chang Yi was trying to do everything.

To Mei Mei, it was clear this wide range of operations wasn’t sustainable. United Biomedical had to be restructured. “Perhaps it was my legal background combined with consulting experience but sometimes it just takes different ways of looking at something to solve it, so I decided to give it a shot,” she shrugs.

She drew up a large organogram on a whiteboard – separating out the generic drugs, animal healthcare and monoclonal antibodies businesses to be spun off into third-party joint ventures. On the diagram she made up names for each offshoot, just for illustration: United Biopharma, UBI Asia, and United Neuroscience. “I was explaining to my mother how we’re going to re-organise things, and just put in placeholder names until we thought up proper names,” she recalls. But Chang Yi loved United Neuroscience, and “just kept saying it. After that, we couldn’t name it anything else.”

A few days before she was due to return to the US, Mei Mei offered to stay for six months to deal with legal issues and help find joint venture shareholders. She took a sabbatical from McKinsey, and soon realised her future was with her mother’s company. “When you grow up and you see your parents work their butts off to try to do good and now they’re about to maybe get screwed, you want to defend them,” she shrugs. She partnered off non-core assets, spun out some departments, and focused on the part of the business that had the most potential. “Chang Yi thinks all of her products are great, and they are, but it didn’t take a genius to see that her vaccine business had the most promise,” Mei Mei smiles.

The vaccine research involved a new field in immunology called endobody vaccines. Most vaccines prepare our body’s immune system to fight off so-called exogenous disease, such as measles or flu, caused by bacteria or viruses entering our blood. Endobody vaccines, on the other hand, prime our immune system to deal with malfunctioning internal parts of the body that it would otherwise ignore.

Endobody vaccines are very rare, with only four approved for the market, two for cancer and two for animal healthcare – one of which was developed by Chang Yi in 2003. This particular drug can completely block the production of testosterone in the body and is currently used as a method of pig castration. “It’s like a teenager’s worst nightmare,” Mei Mei says with a dry smile. “Most men find their partner’s parents intimidating. My mother literally developed a drug that can cause men’s testicles to shrivel up and disappear.”

United Biomedical had other endobody vaccine candidates in development, the most interesting a vaccine for Alzheimer’s. This vaccine had already been successfully tested on small mammals and monkeys (baboons and macaques). Mei Mei wasn’t versed in the intricacies of the biochemistry so decided to get an outside opinion, approaching prominent vaccine researchers. They were blown away by her mother’s work. One investor suggested that she should search for other endobody vaccines that worked in the same way. Mei Mei couldn’t find any. Her mother had created something unique.

Upon this realisation, Mei Mei urged her mother to focus all her efforts on the Alzheimer’s vaccine through the spinoff company United Neuroscience. This was the chance of a lifetime, the opportunity to change the lives of millions. Chang Yi reflected for a few days before agreeing. She asked her daughter to be the CEO of the new company. She would return to the lab and finish the work she had started, she told her daughter. She was going to find a defence against Alzheimer’s disease.

Chang Yi Wang

United Neuroscience’s laboratory sits on an industrial estate at the edge of Hauppauge, a sprawling Long Island town. It’s a low building, divided up into small rooms where machines gently shake organic liquids to create peptide chains for vaccines. On a quiet morning in early March, the only sound is the hum of the machines. The family’s clapboard house is some 20 minutes’ drive away, and it’s there the team hold meetings and throw staff parties. Today there’s a management meeting, with senior people cloistered in the living room. Other staff members sit in the kitchen, picking their way through a vast Chinese banquet prepared by a cook who keeps adding new dishes to the groaning table.

Chang Yi sits at the table, every now and then rotating the Lazy Susan to ensure everyone tries each dish as it arrives. Her short, dark hair is neatly cut and combed, she is wearing a traditional Chinese suit, and she speaks rapidly, peppering her conversation with stories of inventions and inspiring researchers.

Chang Yi has, she explains, wanted to be a scientist for as long as she can remember. She was five in 1957 and living in Taipei, the capital of Taiwan, when her mother showed her a picture of the Chinese-American physicist Chien-Shiung Wu — who Chang Yi calls “Madame Wu” — on the front page of the New York Times. Wu had just overturned a fundamental quantum physics law called conservation of parity. Columbia University physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang had suggested that conservation theory was flawed two years earlier, but it was Wu who confirmed that hypothesis experimentally. “Then and there,” Chang Yi says, “I decided that I wanted to be a scientist.”

She went to the prestigious Taipei First Girls’ High School, and studied chemistry at the National Taiwan University. In 1973, she became the first Asian woman accepted on the graduate programme at the prestigious Rockefeller University in New York. This private medical research centre sits at the centre of New York’s medical science. Weill Cornell Medicine, the New York-Presbyterian Hospital and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center are all clustered nearby.

At Rockefeller University, Chang Yi studied with four academics she still calls her mentors: Bruce Merrifield, the 1984 Nobel laureate for his work on the development of solid-phase peptide synthesis and its potential applications; Henry Kunkel, her thesis professor and a pioneer in clinical immunology; Gerald Edelman, who deciphered the structure of antibodies; and cellular immunology expert Ralph Steinman, who won a Nobel prize (the first to be awarded posthumously, in 2011) for his discovery of dendritic cells, a critical element in the generation of an immune response.

In 1979, Chang Yi joined Memorial Sloan-Kettering, the largest private cancer hospital and research centre in the world, as head of the molecular immunology laboratory. She was 27 years old, making her the youngest faculty member. There she began developing clinical uses for her theoretical work. In particular, she was interested in the role of epitopes – fragments of proteins, five to six amino acids long, that play a critical role in the body’s defence against external diseases.

The human immune system relies on a collection of cells and proteins to identify, neutralise and destroy invaders.

The body’s first two lines of defence are inflammation and the so-called neutrophil cells. Inflammation is caused by damaged cells releasing chemicals that cause blood vessels in the area to leak, swelling the tissue with fluid and isolating the foreign substance. Neutrophils are white blood cells that then ingest invaders and break down their protein chains. The next wave of defence – white cells called microphages – “eat" the neutrophils, extracting fractions of the invading proteins and attaching them to the surface of their cell wall. These fractions are the so-called epitopes.

The presence of foreign epitopes on microphage cell walls indirectly triggers a type of white cell called a B cell. These are produced in the bone marrow and, when triggered, start producing antibodies that clump the invaders together, making them easy targets for T cells, another type of white cell.

After the body has defeated the invasion, it stores a blueprint of the successful B cells and T cells. This makes it much faster at fighting another bout of the same disease, swamping the threat before it has time to spread. Most immunisation against disease involves mimicking an infection by injecting an inactivated or attenuated form of the invader to trigger the immune system – should an infection occur, the immune system will then respond before the person becomes ill.

In 1985, Chang Yi had co-founded United Biomedical with Nean Hu, Mei Mei’s father. Her work initially involved detecting epitopes. The body uses epitopes as a short cut. If you can detect a particular epitope, you know there is a particular pathogen present. Chang Yi was hoping to develop a quick, simple test for HIV using that same mechanism. If you could inject harmless synthetic versions of HIV’s signature epitopes, you could measure the body’s immune response to see if it had already encountered the virus.

“I was working on the HIV virus in 1985 just as a huge argument was breaking out between the French Pasteur Institute and the American National Cancer Institute over who had developed the first test to detect antibodies to the virus back in 1983,” she explains. “They were arguing over tests for the whole virus. I looked at where the antigenic epitopes were. We could synthesise these epitopes and use them to detect HIV antibodies in the blood.”

When her HIV and Hepatitis C tests reached the market, large pharmaceutical companies – which had spent years and fortunes testing for the full virus – claimed patent infringement. The US company Chiron forced her Hep C test out of the UK, but its claim was thrown out in the House of Lords in 1996. By then Chang Yi had shifted her focus to vaccines.

In 1991, she first attempted to develop an HIV vaccine. “The problem is that HIV mutates so constantly and so rapidly,” she explains. “We could devise a vaccine for the strain of HIV we had in the lab, but out in the field it had already changed and the vaccine couldn’t protect people.”

In 1993 she began working on her first endovaccine – partly because no one else was working in the field, and partly because she thought that her work with epitopes was well suited to this type of vaccine. She created synthetic versions of the tiny chains of amino acids that trigger the production of antibodies. In the case of her Alzheimer’s vaccine, this allowed her to develop a mechanism that triggers antibodies to the Alzheimer’s protein in the blood. These then attract T cells that attack any protein with an antibody attached.

But that was to come later. The first endovaccine was directed at prostate cancer – targeting the hormones that prompt production of testosterone, because prostate cancer grows aggressively in the presence of testosterone. And to prove her idea could work, she began working on pig castration.

It took ten years to develop her first proof of concept – a vaccine that tricked the immune defence system of boars into attacking the building blocks of its own testosterone. Without a steady flow of testosterone, the tissues in the penis, scrotum and testicles atrophy and wither away, in effect castrating the animal.

“Drug development is a long and evolving process,” Mei Mei explains. “The immunocastration vaccine started as a human therapeutic, then became a model for testing and building a library of molecules that could work in different conditions, and ended up commercialised as an animal health application. The entire journey was just over two decades.”

In 2003, over 10 years into that journey, Chang Yi read reports that a promising anti-Alzheimer’s vaccine developed by Irish pharmaceutical company Elan had failed in clinical trials. Despite some success in treating the condition, its side effects included inflammation in the brain. The human trials were launched after tests on genetically modified mice had removed clumps of beta-amyloid – one of the key proteins damaging the brain. But during the trials four patients in France developed inflammation in the brain and central nervous system. Further checks revealed eight more cases.

Chang Yi believed her new endobody vaccines could overcome this problem. “The Elan vaccine stimulated the immune system too broadly,” Mei Mei explains. “Your body has two tools to deal with infection – inflammation to trap the invader, and cells that attack and destroy them. The Elan vaccine triggered both those responses. Chang Yi’s vaccines use molecules that are so small, they don’t trigger inflammation.”

Because Chang Yi was introducing small chains of amino acids synthetically created for a specific role in the immune process – essentially just triggering B cells to make antibodies – and because they were attached to a synthetic version of a disease the body already had, they don’t trigger inflammation.

Alzheimer’s also offered an attractive target for her vaccines because the beta-amyloid protein has a very small, very simple epitope that she could mimic. “I could see how easy it would be to do a vaccine better,” she recalls. “Alzheimer’s is such low-hanging fruit.”

Mei Mei with her mother, Chang YiWang, in the family home in Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island

Very few people consider Alzheimer’s to be low-hanging fruit. The condition was first recorded by the German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer in 1906 after he noticed changes in the brain tissue of a patient who had died from an unusual mental illness, with symptoms including memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behaviour.

Since then the disease has risen to become the leading cause of death for women and the second leading cause for men in the UK: combating Alzheimer’s would be a dramatic medical achievement. Half the deaths in the US in 1900 were from infectious disease. By 2010, mortality related to infectious disease had been all but wiped out, leaving the two biggest killers as cancer and heart disease. Over the last 15 years, UK mortality statistics have shown a steady decline in deaths from heart disease, strokes and most major cancers – for men and women.

Over the same period the death rate from dementia – of which Alzheimer’s is the most common cause – has doubled: in part because lifespans have increased, and the effects of the disease increase with age. In the UK, there are currently 850,000 people living with dementia, and 500,000 – perhaps as many as two-thirds – have Alzheimer’s. In the UK, the Alzheimer’s Society expects dementia sufferers to exceed a million by 2025, with an unknown quantity of carers and family members affected.

A total of five drugs are available to relieve symptoms, but they cannot slow or stop the progression of the disease.

In the last ten years, over 100 anti-Alzheimer’s drugs have been abandoned in development or during clinical trials. “We’ve known about Alzheimer’s for over 100 years,” explains James Pickett, head of research at the Alzheimer’s Society. “Forty years ago every form of cancer was incurable – now people are surviving. HIV was almost unknown until 1981, and now it looks like it can be cured. In all that time, we’ve found nothing for Alzheimer’s. It’s a difficult disease, and we’re not even sure if we fully understand its mechanism. What we do know is that it’s a killer and we have no cure.”

Although we don’t know much about Alzheimer’s, researchers believe its effects are caused by two rogue proteins, beta-amyloid and tau – high amounts of both are found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s. Beta-amyloid was discovered in 1984, with tau identified two years later.

Healthy versions of these proteins are important in supplying food to brain cells and ensuring that key chemicals move freely between them. The blueprint for every protein in your body is held in your DNA, which unwinds to allow long chains of amino acids to line up in the correct sequence for each protein needed. When first created, these are long, straight chains, which then fold into compact blobs to function properly.

For reasons that are unclear, damaged beta-amyloid can misfold into a “sticky” form that clumps together in a tangle of fibres – called plaques – that accumulate around nerve cells and disrupt cell communication, metabolism and repair. Tau can also misfold into an abnormal shape and clump with other tau molecules, forming threads that eventually join to form tangles inside neurons, blocking the flow of food.

Both proteins may cause brain cell damage, although researchers aren’t sure if high levels of beta-amyloid and tau cause Alzheimer’s or are symptoms of the condition. Both damaged versions of the proteins can cause neighbouring beta-amyloid and tau molecules to misfold as well – spreading the damaging tangles to other cells, breaking nerve cell connections with other neurons and slowly starving neurons to death.

The risks generally increase with age, but an inheritable form of the disease – early-onset Alzheimer’s – can affect people as young as 30. Symptoms begin with difficulty remembering recent events, progressing to problems with language, mood, motivation and orientation. Patients become isolated and confused as the disease progresses, shutting down physical functions. Some medications can reduce memory loss and aid concentration, but these just boost the performance of unaffected neurons, doing nothing to stop the kill-off of brain cells. There is no known cure. Following diagnosis, life expectancy is typically between three and nine years.

Chang Yi’s vaccine – UB-311 – couples a synthetic imitation of a common disease with a specific sequence of amino acids that are present only in the damaged beta-amyloid protein, and absent in the healthy form. This provokes an antibody response, clearing the tangled proteins away without provoking potentially damaging inflammation.

In January 2019, the company announced the first results from a phase IIa clinical trial in 42 human patients. “We were able to generate some antibodies in all patients, which is unusual for vaccines,” Chang Yi explains with a huge grin. “We’re talking about almost a 100 per cent response rate. So far, we have seen an improvement in three out of three measurements of cognitive performance for patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease.”

Because phase II trials are so small, there’s no statistically valid evidence yet that UB-311 has an impact on cognition and memory, but the lack of serious side-effects is a big step forward. “You’d want to see larger numbers, but this looks like a beneficial treatment,” says James Brown, director of the Aston University Research Centre for Healthy Ageing, in Birmingham. “This looks like a silver bullet that can arrest or improve symptoms and, if it passes the next phase, it could be the best chance we’ve got.”

Mei Mei, co-founder of United Neuroscience

In March 2019, the US Department of Defense invited Mei Mei and her husband, Lou Reese, to explain the vaccine at a conference in Telluride, Colorado. Currently, United Neuroscience is proceeding with phase III trials for its Alzheimer’s vaccine, and has adapted the synthetic peptide technology to create vaccines for the hallmark protein in Parkinson’s disease. Known as UB-312, the Parkinson’s vaccine is just about to enter phase I testing. A third vaccine, targeting Tau, is in the pre-clinical phase. Tangled Tau proteins aren’t just a feature of Alzheimer’s – they’re also found in soldiers and athletes who face repeated or significant head injuries, hence the interest from the military.

Reese, a co-founder of United Neuroscience, was on his way to the airport as WIRED arrived at the door of the Cold Spring Harbor house. He’s got a mop of tousled hair and a contagious energy. “If you’re going after the concept of democratising medicine, that involves new methods of getting the disruptive treatments to patients,” he argues. “We have one vaccine for Alzheimer’s, another for Parkinson’s, another for migraine coming out of the pipeline based on Chang Yi’s building blocks. We have a 50-year vision – to immuno-sculpt people against chronic illness and chronic ageing with vaccines as prolific as vaccines for infectious diseases.” Reese believes that the endobody vaccines are the first steps in democratising medicine. He imagines a future where drones will fly directly to patients, allowing carers or family members to administer the vaccine.

He’s hoping the DoD will be interested in new forms of distribution – including a form of high-altitude delivery vehicle originally developed by the German military in the Second World War. This would use rocket-powered aircraft to fly as high as possible, right to the edge of the atmosphere, so that by the time they come back down the Earth has rotated beneath them. They could travel from London to Sydney in around six hours, carrying the vaccine.

After he’s gone, Mei Mei offers a more grounded — and perhaps realistic — perspective. “What if you went to the doctor and they took a measurement that could record protein levels in your brain?” she begins. “If it’s too high, we give you a vaccine and keep toxic proteins at bay. You could do it in a kiosk in a mall or with an iPad at home, if this could be monitored through affordable blood tests or retinal scans. We’re starting work on an anti-migraine vaccine at the end of this year and the technology can be applied to anything.”

Back in the kitchen, Chang Yi sips tea and avoids discussing Reese’s ambitions. For her, the goal is simply to take what she’s learned with Alzheimer’s and use it to treat everything from cancer to HIV. “If we can do that, I would feel my life’s purpose has been satisfied,” she nods. “My parents gave me the name Chang Yi which, in English, means Always Happy. If we cured Alzheimer’s I would be very happy.”